Are We All Cosplayers Now? On the Evolving Role of Costume in Our Everyday Lives

- Lana N Scibona

- Nov 12, 2024

- 4 min read

I’m not sure what came first. My mom must’ve put the idea into my head. That is, the idea of watching a movie dressed up as one of the characters. All the best Disney films came out in the 90s (termed the “Disney Renaissance” for a reason) so she had many opportunities to outfit her little doll of a firstborn baby in tiny themed outfits. It must’ve delighted her and my grandma to walk into a weekend showing of Tarzan alongside a three-year-old wearing a Victorian bustle and carrying a parasol. But she created a bit of a monster, who went through a Wizard of Oz phase that required a fresh pair of powder blue socks and braids with ribbons every day to watch the movie dressed like Dorothy. Eventually, I grew up and learned how to be too embarrassed to wear costumes on the regular, save on Halloween, despite many years of closet-costuming myself for my high school productions. Luckily as an adult, I found myself again; now, my love for thrifting, fashion history, and dressing exactly like I wanted are an integral part of my identity. Just in time for the premiere of the Barbie movie last summer.

When I decided to show up to the Herald Square AMC dressed as an early 1960s Barbie doll entirely from clothing I already owned, I did it with the full knowledge of my own extra-ness. You have to accept you might be the only one. Well, I guess I knew I wouldn’t be. My friend Elias was also dressed like a Ken doll of the same era. So, the only two, I guess. But then we arrived at a full-scale Barbie party right across from the concession stand. No one could’ve predicted the phenomenon the Barbie movie would be. That hoards of women and LGBTQ+ people would show up in a range of themed outfits, from a simple pink t-shirt to full-scale Barbie costumes. Not only did the movie rapidly gross over one billion dollars in the global box office, but it cemented how our female-dominated culture would continue to transform otherwise passive experiences (going to see a movie or concert) into active, communal events.

The same summer, I attended the Eras and Renaissance tours, also in full costume. But could you even call these outfits “costumes?” The word seems condescending and childlike. (See: new “friend of” Britani calling Bronwyn’s $15k YSL heart coat a “costume” on this season’s premiere episode of Real Housewives of Salt Lake City.) The word implies pulling some random crap out of a bag and throwing it on. But these were carefully selected outfits, not just sported by me and my friends, but every single other person in the stands. Yet, it shouldn’t come as a surprise if the language we have to describe the hobbies and interests of (predominantly young) women is somewhat patronizing. From the dawn of pop culture itself, nearly anything women and girls enjoy is considered to be low on the rung of quality, until decades later men decide it’s art. Among countless examples are Elvis Presley and the Beatles, originally marketed to and subsisting entirely from the fandom of shrieking teenage girls. Flashing back to the summer of 2023, these three female-driven phenomena sky-rocketed the economy, proving the power women have to shift the gears of our world.

A year later, with the explosion of Charli XCX’s brat summer and Chappell Roan’s queer mid-western femininomenon, and the Wicked movie about to hit theaters next week, the trend of being full participants in media moments seems to be charging full steam ahead. So, are we all cosplayers now? Or is this something entirely different?

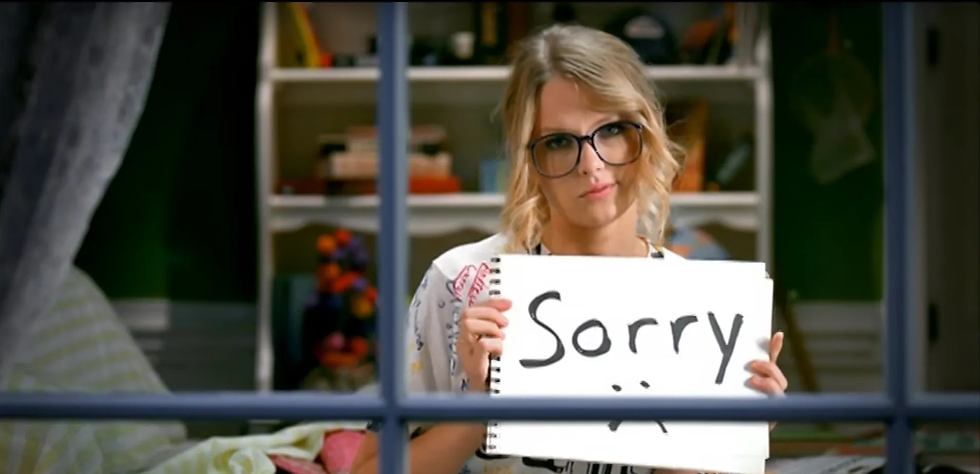

“Cosplay” is a portmanteau of “costume” and “play,” which describes the hobby within the so-called “nerd community” of dressing up as characters from comic books, video games, and other franchises specifically for conventions. Though there is evidence of similar practices dating back to the 1930s, its modern form began in the 1970s in Japan and has exploded around the world since, with an especially strong chokehold on the United States. Besides sharing consumerist tendencies with Japan, American society has another important commonality: a collective struggle with isolation. According to a survey from last April, about 1.5 million Japanese people have “withdrawn from society.” Similarly, 36% of Americans reported suffering from “serious loneliness” in the wake of the COVID-19 lockdown. It would seem, then, that the custom of cosplay brings people away from their thriving but ultimately disconnected online communities and out into the sunlight (or, rather, the fluorescents of convention centers). Though contextually different, the concert and movie-going experiences do share similar processes in recent years. The main reason for going isn’t technically the outfit, it’s to see your favorite pop diva or franchise come to life, but the outfit you assemble is a crucial element. Additionally, these events mimic the same immediate closeness as cosplay conventions. The other attendees at both the Eras and Renaissance shows were so friendly and warm and genuinely excited for each other. I was especially shocked to find how kind the Taylor girlies were, considering the online reputation Swifties have for competitive vitriol (who loves Taylor more, etc). Away from the veil of our computers, we can engage with open, more generous hearts, knowing that the better energy to bring to an event, the more fun it will be for everyone.

Yet, although this new era of “cosplaying” events seems ubiquitous, it hasn’t permeated every fandom. For example, I saw Joker: Folie à Deux in a Harlequin outfit that I once again assembled from pieces in my closet and christened with Gaga’s version of the makeup. I thought maybe other people in the audience would’ve done the same, and they didn’t. I wasn’t disappointed, just surprised. But then again, the crowd did not represent a homogenous subculture like conventions, concerts, or some movies do. We were not a community, merely a movie-going audience, disjointed and alone in our seats. I guess that’s what the whole “cosplay” thing is all about: dressing up as a character and putting your vulnerable little nerd self out into the world, no matter if you stand alone or not. This mentality definitely applies to the maximalist, campy attitude towards fashion many have adopted. Maybe they’re one and the same, a bat signal out into the world that says “This is what I care about. This is who I am.”

Comments